ANZURA’s presentation of The Urantia Book at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

December 3–9, Melbourne, Australia 2009

The Urantia Book is not in itself a religion. Rather, it focuses on the spiritual impulse which gives rise to religions. While there is some truth contained in all religions, it is to the common root of all religions that the book directs attention. It seeks to strip away the fear of God, the dread of sin and transgression, and replace it with faith in the friendly nature of God, who is wholly benevolent and fatherly in his attitude to his creatures. He understands his creatures, knows their limitations, and loves them, and wants them to know him as an inspiration rather than as something to be feared.

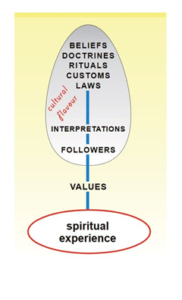

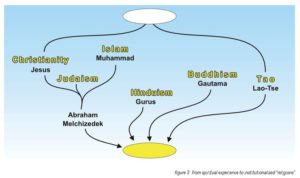

Figure 1 illustrates a generalised view of the structure of a religion. Underlying it is spiritual experience— often the experience of a great man such as Gautama Siddhartha or Mohammed—but there is no conceptual language to express this experience. Man cannot describe his direct experience with God. It remains a marvellous mystery. But it does give rise to values which are remarkably similar, which the book generalises as Truth, Beauty and Goodness.

At this point the followers of the great man—the source of the motivating spiritual experience—begin to try to make sense of that experience, and their interpretations are conditioned by their cultural traditions. These interpretations crystallise in time into the beliefs, doctrines, rituals, customs and laws which reflect the flavour of the cultural civilisation the interpreters inhabit.

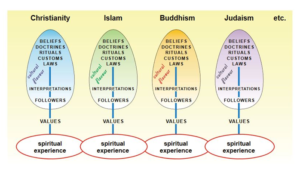

And so spiritual experience and values which are initially very similar become very different institutional religions, illustrated below. The Urantia Book proclaims that the things portrayed inside those egg-shaped ovals are but the external trappings of religion. The essence of religion lies in the spiritual experience underlying that structure. And while some who devote themselves to the egg find their way to true spiritual experience, many do not, but remain stranded in a maze of dogma which is no substitute for true religion.

The book contends that religions and civilisations will conflict with one another until men make it their business to strive for spiritual experience—personal experience of God. It points out that God yearns for man to know him, and when man responds to that yearning he makes God the inspiration of his daily life. Even notions of sacredness and holiness have been exaggerated to the point where they undermine God’s friendliness. The Urantia Book suggests that it is natural and normal for man to bring God into his everyday life as a friend and inspiration, to share his inner life.

The book reiterates again and again that God yearns to conserve all men, and that his attitude is friendly and fatherly. Men can experience sonship with God by including him in their inner life. This personal spiritual experience is what constitutes true religion. In order to help us understand the nature of spiritual experience, The Urantia Book uses many concepts, and some of the most significant are Personality, Thought Adjuster and Soul. Thought Adjuster is something new, but Personality and Soul are familiar. The book does use those terms in quite unusual ways, however.

Personality the book portrays as something far grander and more mysterious than our common usage. Along with matter, mind and spirit, personality is one of the fundamental realities of the universe. It does not evolve. It is a direct bestowal by deity. Evolution resulted in a body/mind system capable of harbouring personality, more or less as our scientists have discovered.

But God bestows personality on that evolved system, which becomes a human person as a result of that bestowal. From the perspective of The Urantia Book, a human being is an animal with personality.

The astonishing quality of personality is that it exhibits some freedom from antecedent causation. As far as we know, it is the only reality in existence with this characteristic. Everything else, matter, mind and spirit, is governed and bound by that chain of causation which originates with God and operates unfailingly throughout reality as cause and effect. But personality, within its sphere of operation, is not so bound. Within a human mind, personality has freedom of moral choice, and that freedom is absolute. God wants to salvage all his creatures—but only if they want to be saved. God does not force us to believe in him, or to accept salvation. As freewill personalities we can choose. It is entirely up to us. God bestows personality, and promptly relinquishes control of it. He retains control of everything else, either directly or through agencies which he originates. He originates personality, but allows it to be free.

In practice, we experience this freedom of will as those moral choices which life throws up at us. We can choose to harbour resentment, or let bygones be bygones; we can choose to seek revenge or to forgive; we can choose to excuse or to retaliate; we can choose to seek God or ignore him. In these moral choices we are free–free to go it alone, or take advice; to love or hate; to learn or ignore–as we choose.

The Thought Adjuster is a new concept introduced by The Urantia Book to describe the influence of God within us. And the book pulls no punches here. This influence is more than just an influence. The thought adjuster is an actual portion—a bit, a piece, a chunk—the book uses the term fragment—of absolute eternal deity, indwelling our mind. I repeat; this is not a metaphor for the influence of God, or for an attenuation of God, or for a disembodied presence of God. This is a piece of the real thing, a chip off the old block, an actual fragment of deity. And it sits in our mind as the indwelling adjuster. It indwells us as a guiding light, to point us Godward, but it is subservient to our will. When God relinquishes control of freewill personality, that means free, and even the fragment of eternal deity indwelling our minds cannot coerce us.

How it works we do not know—it is a mystery. But somehow, without forcing us against our will, it guides us towards the light of life, towards the way of living which leads us Godward. Because God’s plan is so far beyond our comprehension, we have a long period of learning before we can consciously co-operate with it. But the adjuster is there, never resting, working to guide us toward God’s way. And it is not interested in making us too comfortable. Its task is to prepare us for our future life, after our earthly life is finished, and that requires some strenuous learning experiences and energetic choices—things a bed of roses is unlikely to provide.

There really is no logical problem with freewill following God’s will. Our freewill is not being subverted by God’s will. Once we realise that God does whatever is done in the best way there is to do it, there is no problem in aligning our will with God’s. Naturally, we want to do whatever we do in the best possible way too. And it is our indwelling adjuster who somehow or other makes known to us what the best way of doing things is. This does sometimes lead to conflict between what our indwelling adjuster is urging us to do, and what our cultural loyalty requires of us. Our freewill has to referee such conflicts, and they can be confusing. Sometimes we get it right, and sometimes we blunder, but our adjuster never gives up. It keeps presenting us with opportunities to choose—choosing the best way to proceed, or an inferior way—God’s way or some other way.

The Soul is a concept familiar to many religions, but The Urantia Book uses it in a slightly different way. The soul is that part of us which survives bodily death, but The Urantia Book conceives of the soul as an evolving reality, brought into being and growing according to our moral choices.

Humans are endowed with freewill personalities capable of moral choice, and indwelling adjusters are continuously offering opportunities to exercise such choice for or against God’s will. Daily life, in its interactions with others in family, work, leisure, play and so on offers myriad incidents where choice must be exercised. In some manner beyond our comprehension, our indwelling adjuster manages to cast such choices into the form of in accord with God’s will—the best solution—or not in accord with God’s will. Choices in accord with God’s will contribute to soul growth. Whenever a choice is made which is in accord with God’s will, a little bit is added to our soul, and as habits build up which reiterate these choices, our soul becomes a powerful presence in our selfhood.

The Urantia Book thus regards the soul as the evolutionary product of the interaction between two realities at work within us, namely freewill personality and the indwelling adjuster. Though we are not conscious of our soul, or its growth, we nevertheless experience some indication of those spiritual experiences which bring about its growth, but such indications are purely personal and difficult to generalise. However, many people find that their attempts to do the will of God lead them to experience increased appreciation for their fellow men, and greater desire to serve them. Someone once suggested that love is the business of personalities. That love is greatly enhanced by the desire to do the will of God.

In conclusion, I would like to suggest that The Urantia Book fills a great gap in our religious lives in that it provides a concept vocabulary which has been lacking until now. So much of our spiritual striving is unconscious that we have no agreed set of concepts with which to think about our experience. We have not had any reference frame spanning the gaps between the various religious philosophies which allows us to understand what might be happening to us, or which allows us to compare notes with others whose experience might be comparable. Up until now, the mystery of our inner life has been so profound that we have readily become confused and disheartened when confronted by scientific hubris, materialistic worldly wisdom or dogmatic certitude. The Urantia Book suggests a conceptual vocabulary which allows intellectual enquiry consistent with the modern viewpoint and helps us to make sense of religious striving.

As you can see, I think it’s a great book!